THE 1969 RECORDINGS

In March 1969, Kirby Crawford, a geodetic surveyor working on Diego Garcia, taped a convivial evening he and a few fellow Americans shared with a group of Chagos islanders. The equipment he used was an Akai tape recorder [pictured below] which he had acquired in Khartoum, Sudan, while working there in 1966-7. When he moved on it was shipped with a few other possessions to Wisconsin. Posted to Diego Garcia, Kirby later asked his brother to ship the recorder and some music tapes to him. The equipment somehow made it through Mombasa to the Seychelles and from there onto one of the Nordvaer cargo ships that made occasional trips to Diego Garcia. Little did Kirby imagine, on that balmy Saturday evening, that his recordings of the songs of the islanders and the administrator’s speech would provide posterity with a unique cultural record of a moment and a place which has become historically significant and shrouded in controversy. Luckily the recorder still works as well today as it did then, which has enabled Kirby to transfer the recordings to his computer from where their dissemination on the website of Ted Morris has gifted us one of the few authentic cultural souvenirs of Chagos in the late 1960s. A number of the songs and the speech have been transcribed by a native creole speaker, Chris Cuniah. We are very grateful to these individuals for their work in conserving and rendering more accessible this unique cultural record.

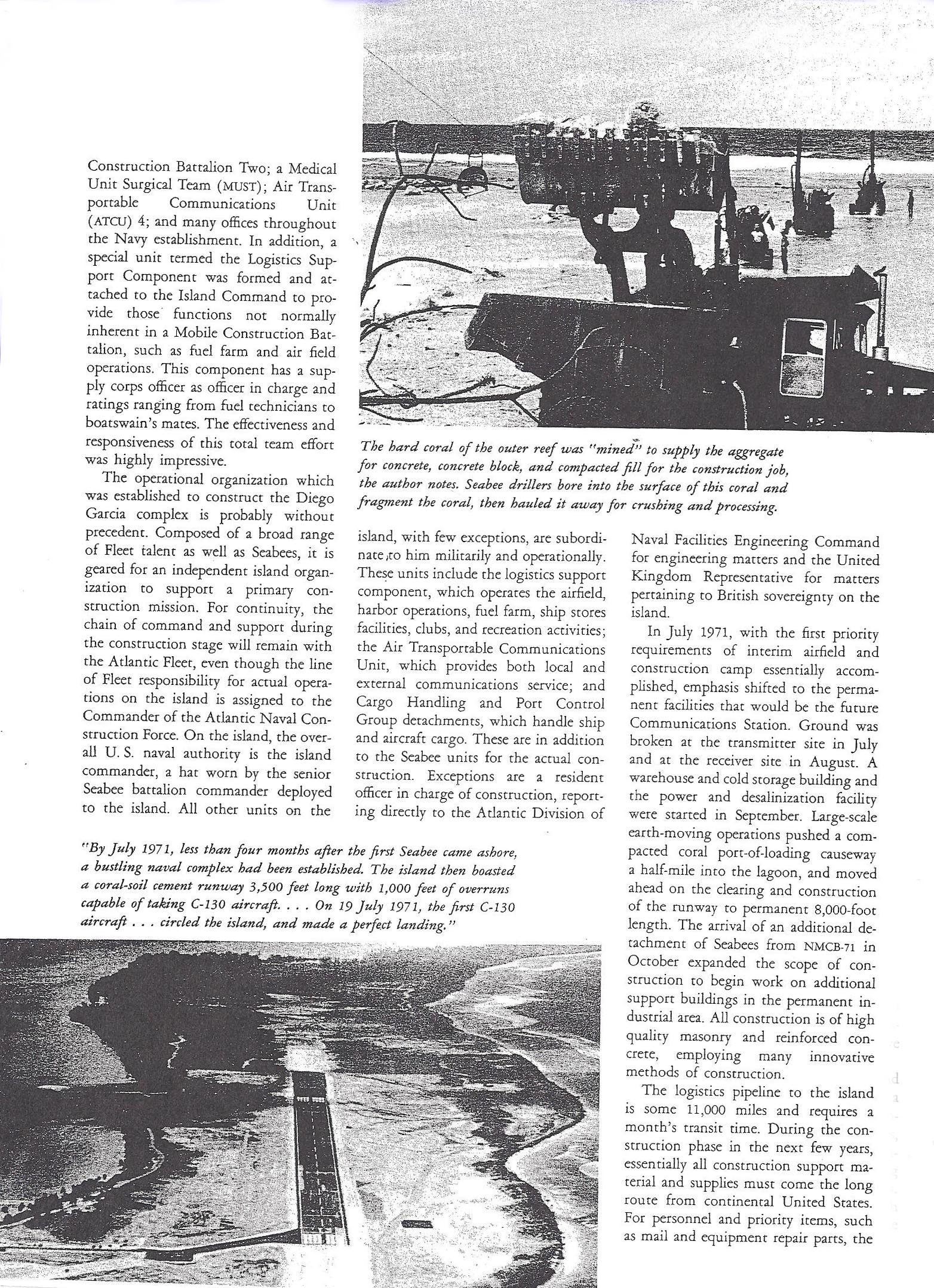

The first song transcribed below, and also featured in the accompanying video is of particular interest because it offers a poignant testimony to the reaction of the islanders to the unfamiliar and frightening sound and sight of military aircraft, their fears for their future, the desire to voice those anxieties, stifled by nervousness about possible reprisal, and the strong belief that the British would protect them. The reference to King George VI [who died in 1952] together with the fact that the airstrip on Diego would not be built until 1971, suggest that the song may have been recounting events that occurred in World War Two. The reference to Raphael, is possibly connected to the island of that name [St Brandon shoals]. However, it seems clear that the islanders are projecting past fears onto the present in 1969, and articulating their uncertainties and fears at that time. A point of interest is the reference to the barking of the dogs, warning the islanders of the approaching planes. Elsewhere in the recordings the barking of the dogs is also heard. The dogs were later all destroyed, so the ‘last bark’ is another aspect of life on Chagos that the recordings have captured.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

PA PLORER – CREOLE LYRICS

Pa plorer, pa sagrin marmail, na pa sagrin le roi George VI finn envoy so zom vey nu.

Mo le cozer, mo le cozer mo pa kapav, mo le cozer mo per tensyon mo gagn enn mari pa larguer

Lundi bo-matin mo tan lisyen kriye, ki li kriye, guet avion la ape fer letur Rafael

Pa plorer, pa sagrin zenfans, na pa sagrin le roi George 6 finn envoy so zom vey nu.

La lahe le le, lehe lehe le le ela la la la la la la…

Lundi bo-matin mo tan lisyen kriye, ki li kriye, guet avion la ape fer letur Rafael

Pa plorer, pa sagrin zenfans, na pa sagrin le roi George 6 fine envoy so zom vey nu.

(Male voice singing: ‘ki li pe roder, ki li pe roder avion la? Li ape fer letur Rafael.’

Ki li pe roder, ki li pe roder avion la, ki li pe roder, le roi George 6 finn avoy so zom vey nu.

Lundi bo-matin mo tan lisyen kriye, ki li kriye, guet avion la ape fer letur Rafael

Mo le cozer, mo le cozer mo pa kapav, mo le cozer mo per tensyon mo gagn enn mari pa larguer

Mo ti le cozer, mo ti le cozer azordi, mo ti le cozer mo per tensyon mo gagn enn mari pa larguer.

Ti le le le la la la, ti le le le la la la

Don mwa la main, don mwa la main charli oh, don mwa la main charli o pas laisse amene la mort lor Diego.

(Male voice: ‘Don mwa la mort Charli, pa laisse nu mort dan Diego’

PA PLORER – ‘DON’T CRY’ – ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Don’t cry, don’t be sad little ones, don’t be sad King George VI has sent his men to look after us.

I’d like to talk, I’d like to talk but I can’t, I’d like to talk but I fear in case I get into trouble.

Monday morning I heard the dogs barking, what are they barking for, look at the planes flying over Raphael.

Don’t cry, don’t be sad children, don’t be sad, King George VI has sent his men to look after us.

La lahe le le, lehe lehe le le ela la la la la la la…

Monday morning I heard the dogs barking, what are they barking for, look at the planes flying over Raphael.

(male voice: ‘what is it looking for, what is it looking for this plane, it is flying over Raphael’)

What it’s looking, what it’s looking for that plane, King George VI has sent his men to look after us.

Monday morning I heard the dogs barking, what are they barking for, look at the planes flying over Raphael.

I’d like to talk, I’d like to talk but I can’t, I’d like to talk but I fear in case I get into trouble.

I’d like to talk, I’d like to talk today, I’d like to talk but I fear in case I get into trouble.

Ti le le le la la la, ti le le le la la la

Give me a hand, give me a hand oh Charlie, give me a hand Charlie, don’t let death come on Diego.

(male voice: ‘Kill me Charlie, don’t let us die on Diego.’

THE ADMINISTRATOR’s SPEECH

On the tape recorded by Kirby is the following speech by the local manager of the copra workers. His jovial exhortation that all at the gathering should enjoy themselves is punctated by a verbal attack on a group present whom, he suggests, have attempted to question his authority. The speech is incoherent in parts, probably as a result of the quantity of alcohol imbibed by the speaker!

CREOLE TRANSCRIPTION

Nu pa vinn la zis pou tap tanbur, pu ceci pu cela. Alor nu tu nu’ne vinn la pu amizer, pu fer ninport ki sen’la amizer, pa vre, ki foder dimoun pu fer kamarad amizer, saken a son tur, n’est-ce pas ? Nu pa bizin dimoun pu vini pu di sa li ceci sa li cela. Alor nu byen kontan zot inn vini, sirtu sa ban gogo*, sa ban gogo* ki zot krwar ki zot kapav bat l’administrateur, mo byen kontan mwa, sa ban boug ki di sa. Mo tuzur silencieux mwa, mo tuzur doucement. Nu byen kontan ki manyer zot’inn fer tanto, Ki tu kitsoz ki zot partu pardonner, pu zot ein… Mersi bucu ein… Don nu ban zoli sanson… si ena enkor enn ti pe… si ena bwar… selma li a zoli pu nu ein.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

We are not here only to beat the drum, for this and that… Well, we are all gathered here to enjoy ourselves and to make sure everybody here has fun, are we not? We need people to have fun, one and all, do we not? We do not need people to come to say this and that. Well, we are very happy you have come, especially those bastards, those bastards who believe they can beat up the administrator. I am happy, I am, that these men say this. I am always quiet, I am always slow. We are happy the way you have behaved this evening. That you have forgiven all. Thank you. Give us some beautiful sega songs…we have drinks… well, it is very good for us, isn’t it?!!

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

SEGA SONG: “Missié Payet”

The following song about the administrator, Mr Payet, is particularly interesting because it indicates how the workers on Diego Garcia made up their own lyrics to describe incidents in their lives, and their feelings about them. A literal transcription is given below, followed by an English translation. The song appears to praise Payet’s intervention in sorting out domestic disputes among the workers as well as relating to an incident which seems to involve a fishing trip to one of the shoals that may have been dangerous [not all of the words can be clearly interpreted]. This song, describing as it does, the daily tribulations of the labourers on Chagos, provides an insight into the mindset of the workers, although it must be borne in mind that the song was sung in the presence of the administrator, presumably as a tribute to him, and may not be an entirely accurate reflection of attitudes towards him. If any residents of Diego Garcia who listen to Kirby’s recording can help to identify ‘M Greller’ and ‘beautiful Adele’, or have any anecdotes of their own, we hope they will add their comments below.

‘Missié Payet’ – CREOLE TRANSCRIPTION

Missié Payet li enn bon regisser, manyer ki nu’a pe fer, mo krwar nu pu fer li move.

Missié Payet pran pesser posson lor banc, la manyer nu pe aler mw’asirer nu pu perdi nu la vi.

U le kozer, mo le kozer, kot mo la caz mo ti le kozer mo pena rezon pu mwa kozer. Si mwa kozer mwa pe travail kot mo burzoi, mwa pe travail kot mo burzoi, l’inn met la pe kot mo la caz.

Missié Payet li’enn bon regisser, la manyer ki nu pe fer nu mem ki pu fer li move.

Mo byen fupamal, letan mo kot sega mo pa kone ki pe passer kot mo la caz, mwa inosan pa kon nanye.

Ou le kozer, mwa galoup kot mo regisser, mo regisser vinn met la pe, vinn guetter kot mo la caz.

Zozo mo mari y’a inpe gro leker, nou met kuraz kot nu la caz, nu pa le sa gogoterie. Mo byen fupamal zot araze zot p’araze mw’asi mo parey kuma zot. Di tou din tou di.

Ti le lehe le lehe, le lehe le lehe le le lehe.

Don mwa la me mo’nn pare, don mwa la me, la manyer ki nu pe fer nu sire nu pu perdi nu la vi.

Rod mari, mari mwa pe rod li, mo pe rod mari li pa ti la, mari dan la caz missié Grellé.

Repone mo la vwa, repone mo la vwa, Adele repone mo la vwa, Adele ma belle ti pu la vi.

Ti le lehe, le lehe, ti le lehe le lehe le le lehe… [2nd female voice]: la la la la la la lala.

Nu’ena enn bon regisser nu pa kone amene, anu chombo li de de la me, si nu perdi nu perdi.

Li enn bon regisser, li enn bon regisser, nu mem ki pu fer li move.

‘Missié Payet’ – ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Mr. Payet he is a good manager, the way we are doing things I believe we will make him angry.

Mr. Payet takes fishermen fishing on the bank, the way we are behaving I can assure you we all going to lose our lives.

You want to talk, I want to talk, by my home I wanted to talk but I have no reason to talk.

And if I talk, I am working at my boss’s, I am working at my boss’s, who has brought peace to my home.

Mr Payet he’s a good manager, the manner in which we’re behaving we’re going to make him angry.

I don’t really care, while I am singing sega I don’t know what’s going on at my place, I’m innocent I know nothing.

You want to talk, I ran to my manager, my manager came to bring peace, come to see by my place.

Zozo my husband who’s a little jealous, nevertheless we take courage at home, for we don’t want any bullshit.

I don’t really care whether you’re angry or not, I’m also just like you, what has to be said has been said.

Ti le lehe le lehe, le lehe le lehe le le lehe.

Give me a hand I’m ready, give me a hand, the manner in which we’re behaving we surely will lose our lives.

Looking for my husband, I’m looking for my husband, I’m looking for my husband he wasn’t here, husband is in the house of Mr. Greller.

Answer my call, answer my call, Adele answer my call, beautiful Adele it was for life.

Ti le lehe, le lehe, le lehe le lehe le le lehe [2nd female voice]: la la la la la la la lala.

We have a good manager we don’t know how to keep him, hold him with both hands, if we lose we’ll lose.

He’s a good manager, he’s a good manager, and we are the ones who will turn him into a bad manager.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

This photograph, taken by Kirby Crawford, shows a perouge outrigger sail boat that belonged to Reginald Payet the plantation manager, who also features [foreground in black shorts].

FRENCH SONG: “Auprès de Toi”

The labourers working on Diego Garcia in 1969 would all have understood the French-based creole language spoken – with some variations of vocabulary and pronounciation on the islands of Mauritius, Seychelles and Réunion, and imported from there to the Chagos archipelago. Many of them would also have been familiar with the French language and would have heard French songs playing on the radio in the Mascarenes and Seychelles islands. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that one of the songs recorded by Kirby Crawford and sung by the islanders is not in the creole tongue, but in French.

FRENCH TRANSCRIPTION

Auprès de toi,

Alice ma bien aimée

Me consoler

Tu me consoleras

Eh bien j’ai fait

Pour ta fête en famille

Moi j’ai su faire

Moi j’avais ni père ni mère

Moi j’ai su faire

Moi j’ai ni père ni mère

Auprès de toi

Tu me consoleras

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

By your side

My beloved Alice

To console me

You will console me

Well I did

For your family party

I knew what to do

I had neither father nor mother

I knew what to do

I have neither father nor mother

By your side

You will console me

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The RAF beachcombing on Diego – courtesy of www.zianet.com

The RAF beachcombing on Diego – courtesy of www.zianet.com

© Dan Urish

© Dan Urish